Documentary On One 1916 Season

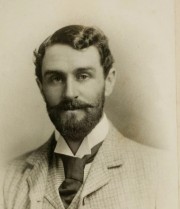

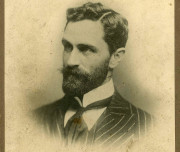

Roger Casement’s Apocalypse Now – Africa & 1916

Executed by the British in August 1916, we know that Roger Casement travelled to Germany during World War I seeking help to fight Britain in Ireland. But Sir Roger Casement was of the gentry class, a son of the British Establishment in Ireland. So, why did he turn his back on his own class and help Irish rebels mount a rising against the British in 1916?

Producer, Colin Murphy, thinks the answer lies in Africa.

Casement spent most of his working life – nearly 20 years – in Africa. He went out as an adventurer and servant of empire, but what he witnessed gradually changed him.

In Congo, he met the writer, Joseph Conrad and told him stories that likely inspired Conrad’s novel, Heart of Darkness – which itself inspired the film, Apocalypse Now.

Then, in 1903, Casement was sent by the British government to investigate the brutal treatment of local rubber workers by the Belgian colonists in Congo. What he found made him rethink his entire relationship with the Empire: he found a civilisation being wiped from the earth, and feared the same could happen to Gaelic culture.

This led to him joining the fight for Irish independence – and ultimately led to his death sentence. And when his colleagues from the Congo campaign tried to have that death sentence commuted, it was Casement’s “black diary” from that same mission in Congo that undermined them.

Colin Murphy visited the Casement childhood home in Antrim in search of the seeds of Casement’s anti-imperialism. There, amidst the paraphernalia of an ascendency family with a tradition of military service, Casement had soaked up Irish history and lore in the library of the Big House, while looking out on Rathlin Island, scene of a massacre by English forces centuries before. The empathy fostered there for the native Irish would be the seed of his empathy for the Congolese; and that, in turn, would reinforce his hostility to Empire.

Casement’s “treason” and “black diaries” brought shame on his family but, in Antrim, Colin Murphy discovered that contact and affection between them endured right up to his execution in London in August 1916. And a new generation of Casements is now embracing his complex legacy – foremost within it, his groundbreaking work in Congo.

Funded by the BAI (Broadcasting Authority of Ireland).

Narrated and produced by Colin Murphy.